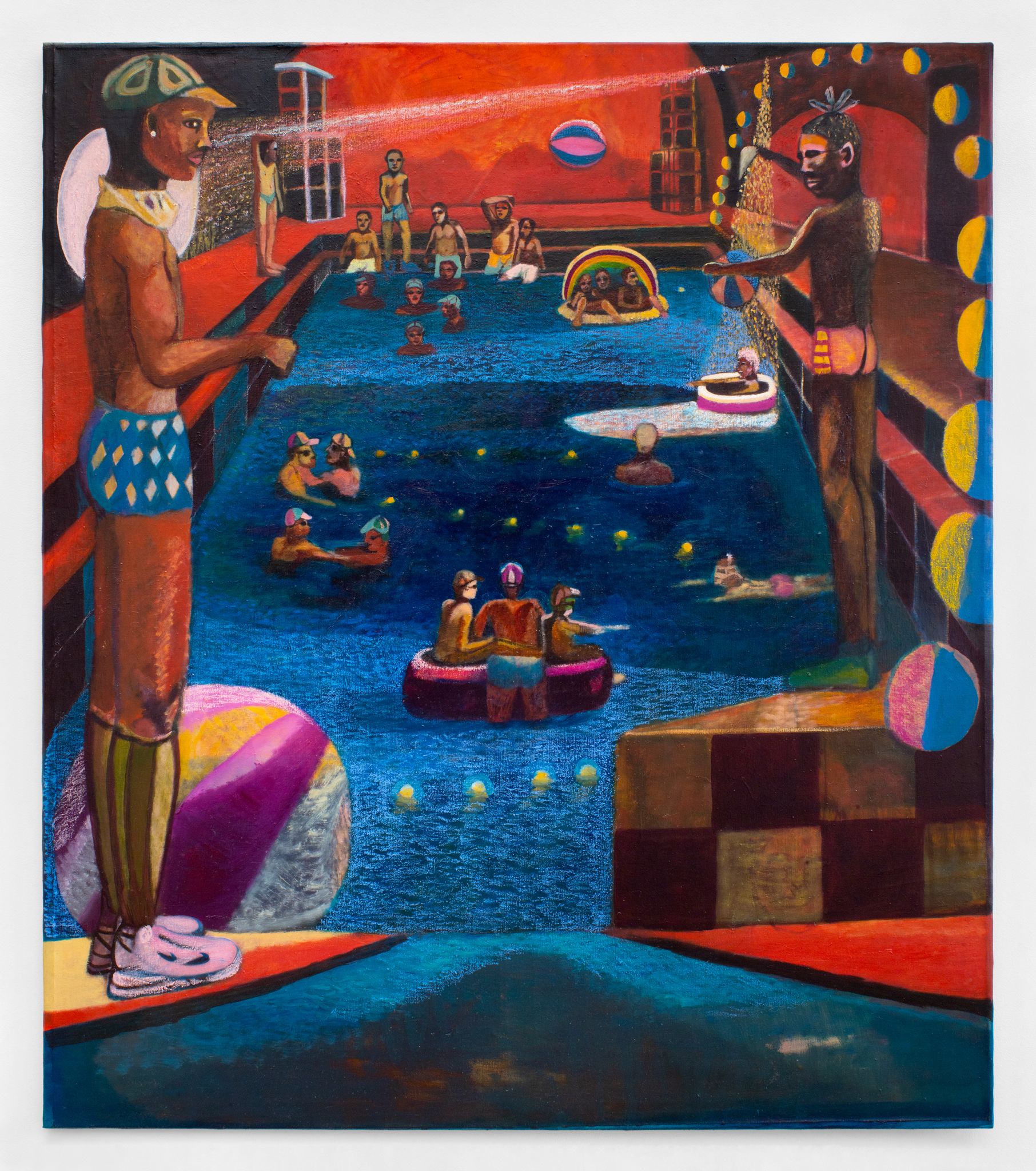

Ryan Huggins, Spiel Haus, 2021, Oil on linen, 63 x 55 inches

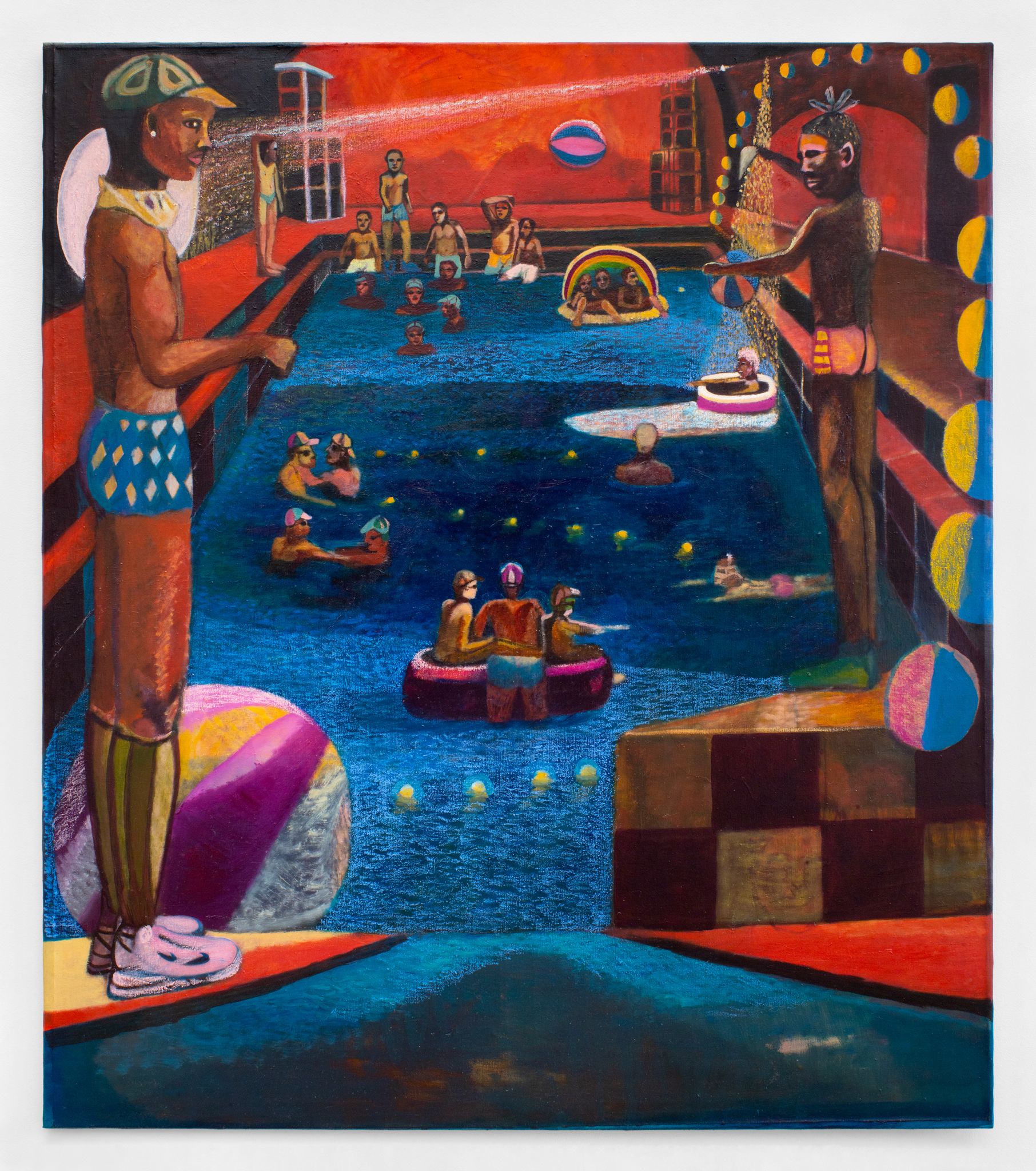

Ryan Huggins, Spiel Haus, 2021, Oil on linen, 63 x 55 inches

RYAN HUGGINS

A Queer Space for Painting

Text by Michel Gomm

From large ecstatic groups of people to individuals in solitude, in Ryan Huggins’ paintings, one might very well be inclined to find one’s way into their seemingly shared world by being perceptive and adaptive to the social situations unfolding. There are no words being said or thoughts written, yet I see them talking, thinking, listening to music, drinking, swimming and dancing in noisy party environments, having fun. Music boxes and TVs are playing, large crowds and crowded places, smell of cigarettes, beer, perfume and chlorine. Why bother inventing specific situations about people interacting, if it was not for the viewer to partake? Yet if everyone remains silent, it is up to the viewer to suggest the right words. For once you are invited to put words into the other’s mouth. Not random words. Choose carefully. The painting, despite appearing to not be familiar with words at all, is not stupid. It will not be able to tell you when you are talking for yourself instead of talking for it, but it will signal to you when you are wrong. Imagine the painting like a visual buzzer that will go off if you stray away from what it wants to talk with you about.

There is something secretive to Huggins’ party depictions. Is the scene shown in “Spiel Haus” a house party? Or where else could this pool party be located? The German “heim” (home) is part of the adjective “heimlich” (secretly/secretive). The sceneries in Huggins’ paintings always, no matter the size of the crowd, have a private feel. The viewer becomes a voyeur—one that is invited to play along, for it is not real but a game. So feel free to feel at home. Your participation counts. No need to feel ashamed.

Whenever only a single person is portrayed, there are still other people present (not being able to tell the specific person does not make it less of a potentially specific person—for example, take a look at thispersondoesnotexist.com). A TV is running. In the unlikely case that no persons are directly shown, it is clear that they are at the root of what is shown. Entertainment such as TV does not create itself. The figure in “Study for Spiel Haus” finds himself in the same room that is about to turn into a buzzing with life party location, or has it been prior to his morning swim? Three people are performing on a stage. The majority of represented people, the (hopefully) vast crowd of spectators is only implied, however they are at the very core of the performers’ experience. Possibly having gone through stage fright, they now find themselves in a moment of self-consciousness and therefore all by themselves. By the end of it, none of them will be able to tell how the others’ standing right by their side did. It does not matter. It is their moment. All eyes on them. Recalling moves. Improvising. Showing off. In Huggins’ paintings, solitude and company do not seem to contradict each other.

Huggins’ paintings have an odd sense of time. There are contemporary indications like the cold TV light enhancing a feeling of loneliness in “Night”, or a vague sense of now as shown in the branding of the front figure’s shoes in “Spiel Haus”. Then there are more subtle, more exclusive clues, such as the reference to a popular Trinidadian fast food chain in “Take away”. The situation is clear to everyone, just not in all its details. Two boys sit in a fast food restaurant. A narrative line is drawn between those that know, those that pick up on the clue and recognize the logo in the back and on the cup and those that don’t know. Depending on that, we take different paths further into the painting, leading to different experiences and different stories told. All of the mentioned contemporary indications might very well refer to something that has happened yesterday or about 50 years ago. (The iconic Nike swoosh logo can be found on shoes since the early 70s, Royal Castle opened the very first fast food restaurant in Trinidad in 1968. Huggins’ lighting doesn’t give away whether the TV is flat or a large bulky block or an actual real object at all, but an idea and therefore only loosely dangling in time and space). The reason they seem contemporary is the context of their display. Painting and paintings both have individual senses of time (sometimes many). Huggins gives clues about time that are simply serving the purpose of addressing a concrete problem: how do I not force a referential medium, such as painting, into the contemporary, while not denying being a part of it and how do I avoid getting stuck in the swamp that referentiality is? If you say “Marilyn”, Andy says “Warhol”. Huggins’ paintings do not mark a clear point in the mentioned timeline. Based on your experiences and liking, there is room for you to choose. The painting can exist in the 80s for one person, in the 2000s for another person, it does not affect what Huggins feels like talking about. He lets you choose and therefore initiates a social interaction through your participation.

The sense of time in Huggins’ paintings is ambiguous. The same point can be made for the spaces he creates, but we will get to this later. Kind of like in a “Choose Your Own Adventure” (CYOA) gamebook (or in German “Spielbuch”) you have to continuously make decisions for yourself that will affect the course of your journey. Throughout the paintings, one gets the impression that Huggins is not really spreading paint but placing it. Short pointillist brush strokes create a sense of movement from a distance, but sit static on the canvas up close, denying entry (for now). These brush marks are more sensual additions to the appearances they formulate, while also undermining them—conveying information about the process, the materiality, the physical reality of the painting and not what it appears to be. What it appears to be can be called the sensum painting, it is the part of the painting that asks you to enter. The real object painting is just a bunch of oil paint on linen, which you can’t enter for obvious reasons. Both exist simultaneously and are therefore meant to be perceived as equally important. We just want to lend the word sensum to illustrate the differentiation between what the painting appears to be figuratively and what the painting actually is. (We know a coin is round. If one was to lay a coin on a table in front of us, it would appear to us to be elliptical. This contradicts the properties we know the real object coin has. Therefore, we can notice that what we see cannot be the real object coin. It is what the coin appears to be and called a sensum). Here we can make a first important distinction for Huggins’ painting. If put in these terms, it seems that the actual realistic part of Huggins’ painting is not the figuration, but rather the parts of the painting trying to contradict their appearance. These parts of the real object painting could be called abstract. What is present in Huggins’ paintings in form of the sensum is a setting. Huggins’ narrative. The unfolding situations mark the playing field for the assumed CYOA, giving implications to what could be going on beyond its appearance. Underlying relations (such as animosities, attraction, possible words exchanged) that are implied cannot be perceived, but only be noticed. For example, you can perceive a weird commonality between “Spiel Haus” and “Dog Days”. The eyes of all people are black. With the exclusion of only a single person. A single approachable person. A single person to empathize with. A single conscious person. A main character so to speak. Or a game character (“spiel charakter”). The protagonist of our CYOA. The entry into our gameplay. From this you can notice that firstly this is indeed odd and secondly you can notice an urge for an explanation.

It’s hot in the paintings. “Dog Days” refers to the hottest days in summer. Clothes don’t really seem to fulfill another function than to be decorative. Guided by their boredom, the two boys in “Take Away”, that have previously endured the first half of the day at school, still wearing their uniforms, ended up at Royal Castle, for a lack of better ideas. The one on the left took a large bite and is now trying to prove his point. The one on the right seems to have a moment of realization. Is this a memory the more mature person in “Night” is recalling? There seems to be a cup from Royal Castle standing by his bedside. The fan in the corner might also point to this situation being located in Trinidad. He does not seem to want to be where he is currently. The TV is supposed to take him somewhere else, but the figure maintains boredom because there is nothing human about the TV’s perfectly flat body of light and therefore, he can’t enter. The TV is inverting day and night, space and time, in an effort to create some excitement, but even put in this way, there surely is none to be found in the figure’s face. Where did the excitement go? At the “Spiel Haus” it was exciting, if it did actually happen, or at least it would be, if it was only a dream and yet to become true. Red carpet surrounds the pool. At best an unfortunate decision by the architects if it was not a dream. What temperature does the water need to have for everybody to be able to party in it all night? Behind the foreground figure wearing the Nikes, there is a drop, a little waterfall, which might not be little at all. If it were not for the beach ball, this drop could be meters high. With the beach ball it looks like centimeters. The ball looks giant compared to the swimmers to its right. If the beach ball is giant, the drop must be giant too. It does not make sense if I think about it. It must be a dream. (A feverish dream? Would I in person of the game character fall down? Or am I about to jump in? Is the water deep enough to jump in? If I was to jump in and swim to the bottom, would I find one?). Even though it might not make sense when actually thinking about it, just like in a dream, it does make a lot of sense looking at it.

To come back to the subject of space, the game characters are the entry points into the actual space that Huggins offers us to explore, interacting as an appearance within a room of information. The goal of the game is to expand, and this way explore as much space as possible. While the game characters Huggins offer stem from the appearances, there is another approachable person to empathize with to be found in the paintings (another source of information to be noticed). Huggins himself. Most noticeable on the surface of the paintings, where the appearances start to dissolve into abstractions. The space you explore in the CYOA thrives on information. Once you find yourself out of ideas on how to go forward, the void in front of you will appear to be a wall (acting as an appearance this equals becoming a wall). A very similar experience can be made online, where a lack of diverse information can lead to a sense of claustrophobia. The algorithm provides recommendations, that make it feel like looking into a mirror, continuously constraining the space you are being presented with to the limits of your liking, and just like in a house of mirrors, it will be hard to escape this cramped space. The interaction with Huggins himself through the medium of painting allows you to do exactly this, to enter a space made from information not limited by the constraints of your own horizon. The more information you manage to get past the painting buzzer, the more light sheds the way of your CYOA. The bigger your playing field, the bigger the space Huggins created for his figures to inhabit.

Why is everybody wearing a mask? And why does it seem that what these masks hide is the part they actually don’t cover (the eyes)? Are these masks supposed to hide or accentuate something about their wearer? The masks fit tightly—they look like hard shell make up. A protective layer with expressive features worn with comfort (the best defense is a good offense). Somewhere in between accentuating and hiding the figures’ character. It remains unclear if some of the more comical mask designs are mocking the wearer or are deliberate choices by the wearer to retain an appearance of sovereignty. The setting seems so private, yet there is a need for protection felt by everyone involved in the situation. In “Dog Days” company can surely contradict tranquility.

Everybody is wearing trunks. On stage, in the pool, indoors chatting with friends. The trunks sit as tightly as the masks. They are barely worn, but a part of the figures’ self. Again, do they hide or accentuate? Throughout the paintings they seem to be a way to avoid the nude while focusing on the body. They serve as a way to introduce more shape and color. They get decorated with patterns and more complex designs, but mostly they are monochromatic. And most of the monochromatic ones are blue. If we take a closer look at “Charade”, we see repeating V-shapes, as well as a repetition of forms opening towards one direction. The half circle of the stage design opens towards the bottom, while the V-shapes open towards the top. In the center of the painting is a large pink V-shape accompanied by the smaller blue trunks. Pink and blue are the two most gendered colors. To be seen, for example, at gender reveal parties. Pink is supposed to signal feminine. Blue is supposed to signal masculine. The three stage performers and the majority of other figures found in Huggins’ paintings appear to be men. The party at the “Spiel Haus” seems to be exclusively visited by men. In the background of “Dog Days”, the room has been decorated with pink and blue balloons. As if it was a gender reveal party. It’s the only painting where women are present too. The women wear long hair, the men wear it short and with trunks. The TV in the back shows two dogs racing. Who is competing? Two competitors, two sexes highlighted, one group, all performers, all drunk, yet still all hiding something (at least their eyes). Cheering. A trophy showing Atlas, an epitome of masculinity, standing on the table. Of course blue. The trophy is being presented. Huggins wants us to empathize with the woman. She does not seem particularly interested in what is going on around her. Or maybe she is disappointed? Other than that, there seems to be a sense of agreement in the room. Is the trophy signalizing who won the race? If it was a boy, would he wear trunks or would he try to carry the weight of the world on his shoulders? The competition has merely begun for the quickest sperm cell.

The bat in “Charade” is a popular figure of Trinidadian carnival. Following is a description from the website of the National Carnival Commission of Trinidad and Tobago:

“Bats sometimes play with clown bands, sometimes as bat bands, and sometimes as individuals. The typical bat costume is normally black or brown, (although white bats are not uncommon) made of swans down with papier-mâché face, teeth, nose and eyes, and fitted tightly over the masquerader's body. While claws are sometimes attached to the shoes, the headpiece always covers the masquerade's head completely. The masquerader sees through an opening in the headpiece where the mouth is located. The wings, which may be as large as 12 to 15 feet, are made from wire and cane, and may be covered with nylon or cotton fabric or the same material as the skin-fitted costume. The player of this character crawls and dances on his toes. He also folds and unfolds his wings and generally tries to imitate the exact movements of the bat. These choreographed movements are called the “Bat Dance” because they mimic a bat’s movements.”

It seems like what the performers are trying to do fits very well the title of Thomas Nagel’s 1974 essay “What Is It Like to Be a Bat?”. In his essay, he proposes the following idea:

“If the subjective character of experience is fully comprehensible only from one point of view, then any shift to greater objectivity—that is, less attachment to a specific viewpoint—does not take us nearer to the real nature of the phenomenon: it takes us further away from it.”

Because the viewer is invited to make subjective decisions that alter the course of their gameplay, Huggins avoids conveying ideas that are limited to the extent of his own horizon, while also enabling the viewer to come to conclusions that are exclusive to subjective experience. He initiates a discussion instead of dictating from a position of power. Answers are neither to be found in the illusionary space the figures are depicted in nor in the real space one encounters his paintings in. Huggins undermines the binary of abstraction and figuration, and by doing so, creates a third space made of information—a queer space so to speak. Just like the paintings serve as a medium for Huggins to reach out to the viewer, the viewer themselves in the CYOA mediates between the abstract and the figurative side of Huggins’ paintings, engaging with queerness formally and narratively. By doing so, they create a new space, in relation to the sum of information Huggins offers, exploring and discussing gender, queerness, sexuality and social pressure, in a playful way.